For my video on Law and Freedom, click here

No one read old books anymore. The ancient voices had no resonance in the modern world, the age of absolute equality and freedom, a world of universal democracy in every institution of society; a society finally liberated from the constraints of hierarchy and tradition.1 Any trace of monarchy, aristocracy, or hierarchy was intrinsically evil because, as everyone had been taught, such forms of government were by nature anti-democratic and anti-egalitarian. Only democracy was legitimate, just and, even, evangelical, the only true secular religion. The only religion at all.

The revolution had been both radical and metaphysical. Equality was not limited to the material world. Equality even applied to men and God. As it was impossible to know if God existed, they said, the people should act in the temporal realm as if God was dead, as if he had been dethroned. It was the people who had dethroned him.2

The good people of this Utopia recognized that authority in pre-modern times had been based on a dark, primative mythology, which acted like a cement, or a toxic glue, to keep people together against their will and the old rusty clock of the social order ticking. This myth included the quaint notion that God or nature or the “old ones from time immemorial”, whatever you prefer, had divided up human society in accordance with functions, responsibilities, aspirations in life, equalities and indeed natural inequalities. Equality, they believed, only applied to likes, which of course created false hierarchies based on power. People hadn’t been liberated yet by the sacred revelation that equality was the skeleton key to open every political, social and metaphysical door. It was hard to imagine a world back then, before the modern one, in which Equality, Equity and Inclusion wasn’t yet seen as the answer, literally, to everything. Instead, in the place of DEI, were those preposturous falsehoods. No one believed those anymore.

The dusty, some acid soaked, but invariably neglected volumes were from pre-modern times, from the Classical, Medieval, Renaissance and post-Renaissance periods before the modern world, before the expansion of the franchise and the great migrations. The subjects of these neglected texts were art, urbanism, the law, music, philosophy, history, the structure of society, the life of princes and burghers, peasants and saints, and with few exceptions, they were marked by a respect for the way things were in their created status, respect also for the way society was organized and the world was structured. This respect for what they thought was reality, for the inherent principles of the universe, is what separated the pre-democractic from the post-democratic world.

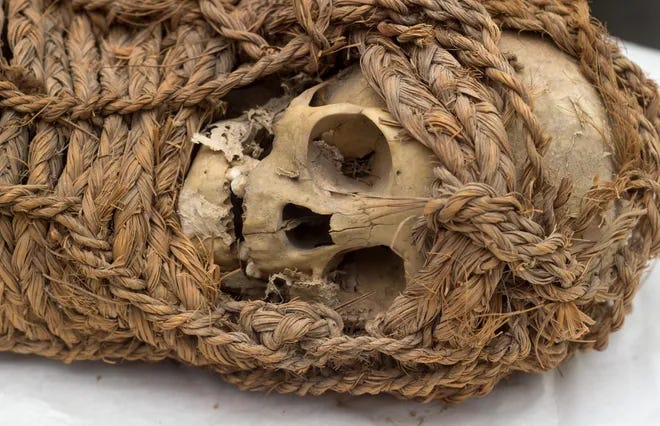

Everyone now accepted that authority was bad, or should be exercised only with the general consent and, even so, called on for inspection only on the rarest of occasions, like the mummies of the Inca ancesters, dusted off and patched up for display, during designated festivals and then holed back up in their niches. The use of authority was also always subject to myriad exceptions to ensure the greatest possible individual freedom. The sovereign is he who makes the exception.3 Freedom had finally triumphed when put under the exclusive protection of the modern state. The modern world was one in which authority had given way to an absolute freedom, or what some stodgier types called ‘permissiveness’. Certainly, you couldn’t yell, “fire in a crowded theatre,” but the individual was otherwise free to make his or her or their own truth. The authority that in Rousseau’s words, had held the individual in chains, had been hacked off. The mythological authority that was needed among more primitive peoples, had been liquidated in Western societies, such that it was now a tiger with no teeth, weak or no longer exercised at all and kept in a small cage for display by the curious. Authority was an exhibit in the modern version of a Victorian London zoo, confined to a small, dismal, enclosure. Authority had been a humiliating agency, counteracting and repressing the individual’s genuine desires and sacred freedom. Now, freedom reigned and utopia was the offering made to every citizen of every Western state and from there, soon, to one unified world.

But as the people of the land soon realized, although ancient forms of mythological authority were effectively neutred or banned outright, this didn’t mean that authority drifted up and dissipated in the upper atmosphere. Authority, even in a society of absolute freedom, doesn’t cease to be; it changes and mutates. You could feel it, that new, modern authority. But this was for the good, this time, instead of evil, they said. The more freedom was promulgated, the more laws were needed to protect it from the reactionaries, and the more police and special agents were deployed to enforce it and monitor those who spoke and wrote against it. Freedom it turned out needed a tyrannical government to protect it. Modern people understood this as a natural byproduct of freedom, its effluent, a beneficial waste product like fluoride, and weren’t troubled by the meddling of the state in every aspect of their lives at all.

Authority had always entailed inequality and hierarchy. What thinkers on politics and the law for centuries had meant by a “well-ordered society” to be one in which social orders observe their hierarchical place and their general subordination to the common good. Institutions confine their functions to their specific areas. Universities, did not meddle in politics. The state didn’t meddle in the family.4 The limitations are freedom had now replaced it. But, funny thing, a new kind of inequality seemed to take the place of the old kind, those who perhaps loved freedom even more than most, a new hierarchy of bureaucrats, media, therapists and corporate elites, had formed spontaneously, to monitor freedom and to ferret out its enemies, and remind the people to be vigilant, which was the price of freedom5, and to report anyone, co-worker, friend or family member, who spoke scary words, or could be a threat to freedom and democracy — for their own good of course, and for the common good of a free society. Thank goodness for that. It was reassuring to know the government cared.

Authority had been seen in the pre-modern era as a positive or good thing with a given purpose, usually some ancestor’s idea of what was right, virtuous with the primary condition of carrying out the social objective of society. It was positive, directing towards the good and fundamentally rational. Now, freedom and equality alone would be the guide; freedom and equality would provide the full spectrum of purpose and be the social objective of a free and democratic society. Freedom was a foundational good and nothing else mattered nearly so much, at all.

But as always, there were scary things on the horizon. There always seemed to be some new threat, some new crisis, some new emergency. As it turned out, a world without inequality and hierarchy, or least the old fashioned kind, was proving to be challenging. Something was screwing things up for the good law abiding people of the land. It wasn’t that anyone who wasn’t a criminal opposed perfect freedom. It was, well, just proving difficult to work out all the kinks. And finding out who was throwing the wrenches into the perfect machine was also a time consuming process for the reformers. Several generations of activists had already been born, died, and buried, without reaching the promised land, with plenty of wreckage left along the way. This wreckage wasn’t the fault of activists of course. It was just going to take a little bit more time, with the torch now handed off to yet another committed generation rising up likes insects from the mud, to resume the struggle, fighting heroically even with no obvious end in sight.

Certainly, the historical records seemed to show that when the old authority broke down, so did the society. There was that episode after the conquest of Mexico, when the Aztecs, accustomed to fearing their princes and priests and spending their lives in dependence of idols and sacred practices, found themselves all of a sudden under the authority of the Christian system, which they did not understand. The Indians complained that freedom from the old ways had left them, “lax with sin.” Asked why, the Indians replied, “In former times, no one did his own will but what he was ordered to do; now the great liberty has done us harm, for we are obliged to fear and respect no one.”6 A similar process occurred after the great migration of Blacks from the South into Northern cities as cheap labour, or when in the 19th century another wave of European immigrants arrived in the United States at Ellis Island, finding themselves free from one tyrant, only to be beholden to new ones, usually in the form of their own “liberated” people.

In periods where authority weakens, a sure sign of the impending collapse is that the enemies of authority redouble their attacks upon it, through its former friends who saw the writing on the wall. The universities, the media and even the churches hastened the process, switching to the anti-authority language and style, indistinguishable from the language of their former enemies.

Freedom abhors any institution standing between the individual and the great protector of the individual, the central state. And without ordered liberty, new institutions entered a mad scramble for power, there being no structural limits. Where freedom triumphed, all could see the loosening of the institutional ties upon which civilization had, until modernity, traditionally rested.

This was particularly so with the family. The ethnographers suddenly discovered that families were not only of one type, but could be differently structured: they could be matriarchal, extended or sexually tolerant — followed soon after by the total sexual freedom of the modern family, and everything that entailed.

Next, the psychologists discovered those hidden, subconscious motives, creators of tensions, resentments, conflicts on the part of parents, children, the male and the female, and the subjective nature of sexual identity. The main thrust of the sexual revolution was the family’s sexual freedom and sexualization: all taboos lifted — against divorce, pre-marital sex, early sex, adultery, homosexuality and same-sex marriage and adoption, incest and abortion and more recently steps to legitimize “minor attraction”. What had been an issue of morality was transformed into sociological phenomemon, a matter of ever changing scientific expertise, rather than immutable law or the management by the jurists and a priestly class. The traditional mediators of father, teacher, priest and judge, were replaced by the psychologist, therapist, bureaucrat and committee. Some whispered, in dark smoked filled rooms, that when the revolutionaries had talked of liberty, they really meant liberty to pursue unrestricted sensuality and to justify the free course of the worst passions and the most pernicious errors. Others whispered back that they should lighten up.7

Legislators and judges had no choice but to yield, purporting to change or declare the laws to be entirely consistent with and a true reflection of goals of modernity, as it always really should have been if the legal system had not been so occupied, colonized, intolerant and backwards. This gave the so-called laws an offical stamp of approval to the fait accomplit.

The media…. ah the media. Don’t we see through them now. But back then, they exposed the “right of the people” to be informed, provided with the background “sonority, the new values, the incitement through round tables, statistics and sob stories.”

And so, freedom, with the gentleness and compassion of Sherman through Goergia, had marched through the institutions, but also the entire population, including your cousin at the dinner table next to you.

… Had marched….

… Through the authority of the family.

… Through the authority of the school.

… Through the authority of the church.

… Through the authority of the courts.

On and on.

Authority hasn’t gone away, but had now mutated in curious ways.From the authoritarian, society had moved into the egalitarian. From the customary/institutional, the people had moved into the contractual and fraternal. From rigid rules and traditions, into codes and statutes revised, and reinterpreted to ensure so-called rigidity had been replaced with the loose fitting, the reasonable; and those charged with enforcing the new laws encouraged by the state to ensure they were applied — or ignored — as the case may be, depending on the circumstances, depending on what was equitable and inclusive, and mindful of historical or systemic injustice.8

And as bad as it sounds, the tension building…. that’s the end of the story. Nothing happens. Nothing ever happens. That’s the way it was, and that’s the way it remained.

Thomas Molnar, one of the great philosophers and political thinkers of the late 20th Century, saw through the cult of progress and of freedom, as an social end in itself, in his classic 1976 work, “Authority and Its Enemies”, to which I am indebted for the above parable or what we might call this “unfinished story”.

Molnar, born in Budapest in 1921, saw that these modernist cults and their attack on legitimate traditional authority was only producing a kind of institutional anarchy, held together by an increasingly authoritarian machine, devoid of humanity or anything resembling a higher moral code or restrained by natural or traditional morals, laws and customs. The machine just existed for itself. Freedom he saw was producing the exact opposite of what it had promised, but not only was there patently LESS freedom — not MORE — but the evidence was plain, everywhere, of social chaos, disenchantment and outright misery. Although one can dream that the chaos will one day be replaced by a kind of Augustan return to order, despotism seems at present to have the upper hand.9

Molnar died in 2010 and could only have seen the tip of the iceberg of progressivism, much of which was still lurking below the surface, its seemingly unstopable momentum mostly concealed. Since the Age of Trump, Covid and Globalism in its full panic mode, things have gotten considerably worse, but entirely along the lines Molnar described, with its bleak trajectory apparently unaltered or even unalterable.

The key characters in the drama of legitimate authority were the father (in the case of the family), the teacher (in the case of the school), the priest (in the case of the church), and the judge (in the case of the courts). All served under pre-democratic societies as mediating agents, intermediary powers or sources of legitimate authority that served to shelter and protect the individual, family and society from the state or king or oligarchy as the case may be. Molnar argued that the quest for a utopian, universal polity have created the crisis of authority we face in the modern world. What the progressives don’t and will never understand is that authority is not just the cement that keeps society together in a brutal Hobbsian way, but depends on a balancing of the true natural inequalities that are inseparable from our humanity and the reality of life in this world. Society depends on the implementation of a value hierarchy, which allows us to rely on each other in the “vast give and take of social, material and cultural transactions” that make up a happy, resiliant society. The alternative is distrust, fear and even loathing. Molnar concluded that the authoritarianism associated with inequality was far preferable to the totalitarianism, the inevitable consequence of forced equality:

Thus, the rational nature of society, which, we repeat, implies the acceptance of inequality as both natural and a means of preventing a totalitarian steamroller reducing everyone to serfdom, contradicts the premise that all men ought to [be equal, e.g., own the same amount of property].10

Absolute freedom works the same way removing the Earth’s atmosphere would work: not very well. Freedom as a goal in itself also seems invariably to involve, as we have seen so often in this series, a concentration of power in the central state and the removal of intermediary institutions:

“[In] every case the crisis can be shown to spring from the attempt to eliminate the mediating agent and reduce the ‘space’ between the source of authority and those supposed to obey it, to zero. Father, teacher, priest, and judge see their roles indefinitely weakened; the trend is in each case for an elected committee to take their place, itself to be replaced in fine by the individual’s consciousness. The child, the pupil, the believer, the criminal are credited with possessing the best insight into their own motives (as if this were the decisive point) and therefore the only correct judgment on the merits of their acts. In reality, the systematic critique to which the mediating agent is today subjected, and behind him the entire concept of mediation, indicates that the critics reject the notion that there is anything to be mediated: natural law, divine will, or a body of knowledge.”11

The cult of freedom was not replacing authority. From the teacher, it passed to the most violent and dysfunctional of students. From the father, it passed to the most inexperienced and mentally unstable of children, encouraged by the state to self-create an identity.12 From the judge, it passsed to the most intransigent of criminals, the incorrigible repeat offenders, excused for all time from traditional penalties that flowed naturally from a crime committed, like murder, or rape or treason, with any punishment now obliged to be justified on some utilitarian grounds, while natural penalties like death, for a crime like murder, are simply deemed by the machine to be “not allowed” as an unjustifiable assault on the sanctity of freedom or “dignity” of the person.13

As it turns out, the mutated authority under the progressive regime is just as, if not more, reliant on myth, than in traditional societies, but in this case a myth is the real Big Lie, that tells us, “Everything is actually getting better, trust us, despite what your fallible senses may be telling you.” Democracy it turns out is a great secular religion dependent entirely on faith and fantasy.

“Legal freedom” properly understood is a quality of civilization, much like health is a quality of good food, clean water, exercise and good genes. Freedom pursued ‘though the heavens may fall’ (Fiat justitia ruat caelum), may not actually bring down heaven (which the materialists don’t believe in anyway), but does seem to bring down civilization (which they may or not believe in, depending on who you ask).

Legal positivism, that the state is the sole source of law, can offer no resistance to totalitarianism, as “only an appeal to the intent of the law, contained in natural law (the right of the community to protect itself) may save society from chaos and disintegration. To pretend that the positive law alone exists, as our judicial tradition holds, is to tolerate aggression by armed men and to disarm our community’s natural protectors.”14

Next time we will look at the main values once understood to be expressed in the concept of “Legal Freedom”,15such as those familiar notions of freedom of contract, the right to property, free speech and the press, freedom of association, freedom from want, and the like, and consider how the promise of “legal freedom” is doing these days. Not very well as it turns out.

Molnar, T, “Authority and Its Enemies” (Routledge, 2017; originally published by Arlington, 1976)

Correa D. Oliveira, P. quoted by Shephen, P., “Remembering Plinio Correa de Oliveira (Chronicles, December 2024) at 22 et seq.

Schmitt, C., “Political Theology: Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty” (1922). Schmitt argues that sovereignty is defined by the power to decide when to suspend the normal legal order, particularly in states of emergency of exception.

Molnar, supra at 116

The saying "The price of freedom is eternal vigilance" is often attributed to Thomas Jefferson, www.monticello.org. It may in fact have originated with John Philpot Curran, which Jefferson paraphrased: "The condition upon which God hath given liberty to man is eternal vigilance".

Molnar, supra at 22

Oliveira, supra at 23.

Molnar, supra at 51. As Thomas Molnar forsaw, “Tomorrow another class of people may be so favored [with exceptional status] by the same or other ideologues, enemies of authority and subverters of institutions.”

Molnar, supra at 125 et seq.

Molnar, supra at 53

Molnar, supra at 50

John Dewey wrote that “the classroom ought to be a ‘small replica of our democratic society’ … and, paralleling his thoughts, his disciples and other thinkers have been trying to equalize the status of teachers and and pupils (professors and students). No doubt this can be done, but only at the cost of undermining the school’s implicit objective, education, instruction” (Molnar, supra at 38.

Molnar, supra at 51

Molnar, supra at 131

Lloyd, D, “The Idea of Law” (Penguin, 1985) at 142 et seq.