For the prequel to this chapter, click here

For the beginning of the Argentinian Saga, click here

Inspector Furriel looked up at Lieutenant Montiel, smirked and tossed his fountain pen onto his grandfather’s 16th century carved spanish oak writing desk. Montiel did not need to hear again of the desk’s, “amazing provenance and historic and literary significance,” as Francisco had told him so, many times, in the most extraordinary depth of detail — befitting the Chief Inspector of the Policía Federal Argentina or PFA — over coffee or a Fernandito, and in those uncomfortable moments of silence when nothing more is left to be said, and when speaking, the internal voice and dreaming lose their natural boundaries.

“Visitors you say?”

“From Lima,” added Nicolas.

“Our killer certainly has been around. It is time we put this canary in a cage.”

The PFA was the national civil police force of the Argentine federal government, but also served as the local police force of Buenos Aires. The PFA's headquarters, known as the Departamento Central de Policía, in the Montserrat section of Buenos Aires, was located is a massive 12,000 m2 (128,000 ft²) structure designed by Juan Antonio Buschiazzo, engineered by Francesco Tamburini, and approved for construction in 1884. Furiel and Montiel walked down the main hallways, shoulder to shoulder at a brisk pace, utterly indifferent to the designer’s eclectic tastes, the Baroque and Rococo influences, the many patios, embellished with palm trees and exotic birds and beasts, both mythical and real, of all description.

The door to the interview room flew open as if kicked in by a large man of considerable strength. And so he was. A man in black, nearest the door ceased, for this instant, flicking his pocket watch, open and shut. He rose in military style, as if for inspection. His colleague, also in black, remained indifferent to the intrusion, continuing to read the day’s edition of the Razon, the city’s main newspaper.

“Sit down, sit down,” snarled Furriel. The pocket watch clicked shut. The newspaper closed, folded and rested on a knee.

“What do you know about this Caron murder?”

The watch clicked open. He rose again. “Sir Inspector, I can advise that we are here on the instructions of a Messieur G, who has retained us in, what you would call, a missing person’s matter.”

“You are private investigators?”

“Yes,” looking over to his right.

“Do you mind if I speak for both of us?”

His colleague removed his black hat, placed it over the newspaper, shut both eyes and nodded his approval, with evident pleasure.

“You see this was a joint retainer by Messieur G and by a person who wishes to remain,” clearing his throat, “… anonymous. My office is in Montreal, Canada. My dear colleague … friend …. operates out of Beirut. Our principals have instructed us to cooperate and share the results of our investigation with each other and with the investigating authorities, if common decency requires, and provided the terms are mutually beneficial.”

“Go on, go on, none of this is of any interest to me. You have information or you don’t, get on with it,” said Furriel his unblinking eyes now fixed on the man with the watch. A buff-curtained window, 10 inches open, let in from the courtyard a current of sickly air, faintly scented with a mixture of rotting seaweed and diesel fumes.

“Certainly. And I must repeat, we are instructed to provide this information obtained at considerable expense by our clients, in the public interest…”.

“Go on…”.

“… As we believe it may be of assistance in solving the case … Yes, right.” The watch clicked shut, retreated to a left pant pocket as a note pad was retrieved from the right, inside jacket, flipped open. He began to read from his notes:

Deceased was seen in the company of a member of the Puerto family, a Justiniano Puerto, son of the late Felipe Carrillo Puerto, as well as an American, Ellen James, archeologist by trade. It is suspected the deceased accompanied James to the Ek Balam archeological site in the Yucatan, purpose unknown. Justiniano Puerto, fugitive, location unknown. James seen in the company of known antiquity dealer, a Messieurs D. May be transacting in black market. Deceased admitted to hospital in Valladolid by James, apparent snake bite. Disappears. No records of hospitalization exist. Body found in Oaxaca. James observed at the Country Club Lima, with a gentleman believed to be her fiance. Purpose unknown. Contact lost on route to Cusco. James subsequently relocated in Lima and followed to Lima airport one week ago. Boarded flight to Buenos Aires.

“We have not located her in your city as yet. My principals are of the view time is of the essence, and thus our visit. I am also instructed to make one request of the investigating officers… that would be you. The request is that after the imminent arrest of the suspect, by competent authorities, whose name Mr. Montiel advises may be a Juan Perez, that we be permitted to view the possessions of the suspect. We may then be able to provide further information to authorities on any stolen property in the hopes of perhaps seeing that such objects are returned promptly to their rightful owners.”

“Uh hum,” noted the Inspector, suggesting an affirmative without saying so.

Montiel rubbed his chin, squinting his yellow-green eyes. “Why the devil is this archeologist here? What is her game?”

“A coincidence, no doubt,” spoken dryly. “No hospital records? That is curious.”

“She has no known interests in the city,” added the men in black, in unison. Thus, our visit in the hopes you have leads in this regard.”

“Oh, perhaps she does indeed have interests here. The suspect! Antiquities! Black markets! A dead Frenchman! A man who kills in his dreams! It all makes perfect sense! We need to get to this Juan Perez before she does, and prevent whatever transactions these two co-conspirators have concocted. They don’t know who they are dealing with.”

“We tried to pick him up yesterday,” added Montiel. “Someone must have tipped him off.”

“Tell Raquel if she wants our help, she had better find him.”

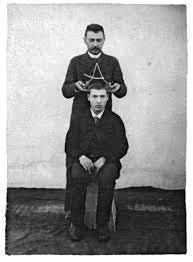

The Inspector rolled his swivel chair to face the wall, looking up with pride at a photograph of Agustin Drago, framed in silver, the city’s famous forensic doctor, sent to Europe to interview the Frenchman Bertillon in Paris in late 1887. Upon Drago’s return, he persuaded the city’s police authorities to implement the Bertillonage method and to open an Anthropometric Office at headquarters. The implementation of this latest and most promising system of identification of suspects, made Buenos Aires a leader in the pursuit of “order and progress” and in the realization of the ideas of Auguste Comte. Anthropometrics relied on the unchanging character of certain measurements of parts of the human frame, such as length of the right ear and the width of cheeks. By a pain staking cataloging and recording of this data, the investigation of crime could be further systematized and standardized and the apprehension of suspects made more safe, efficient and effective.

Beatrice could have noted a similar photograph of Agustin Drago, carried by the Judge wherever he travelled, and displayed prominently in his cabin on the Don Pedro. She did not, as she had no cause to do so in those hours before leaping overboard after Alba. Had the opportunity arisen, she could have observed an uncanny resemblance between the tall, dark, black and white image of this long dead Argentinian forensic doctor, symbol of the triumph of the scientific method in the war against crime, and the tall, dark, shadow of a man she took to be, or who at least presented himself at the most fortuitous moments as, a loyal servant of her former master. That information was, in her current circumstances, no longer of use to her.

There was a gasp, as if from a dream. And then it all became calm and domestic. He felt at ease. Caron pulled up a simple wooden chair, lower to the ground than he was used to, but comfortable nonetheless. He remained fixated on the game of hounds and jackels. The chair was elaborately adorned, lions, chariots, the fury of the hunt, carved into the back. The lion legs ended in lion paws, with a gold inlay of eagle's wings.

Queen Nefertiti, very much more beautiful than he had anticipated, the famous bust doing her no justice. Her dress, the kalasiris, elaborate and detailed, tight-fitting and accentuating her figure, graced with intricate beadwork and jewelry, gold thread and precious stones. Comparing the living Nefertiti, to that famous bust, Caron thought her beauty was magnified infinitely by the natural living motions peculiar to the human female, when engaged in a thoughtful, pleasant, stress free exercise. Such was this moment at play, with her young son Tutankhamun, his head displaying the side lock of youth.

“My jackels have your hounds at bay!” the Queen taunted, leaning forward, cat like, across the game board.

The young prince, defeated again, sighed.

“Come close, closer. I have something to tell you that I know will please you.”

The young prince, slipped from his chair, and crept into his mother’s smothering arms, teetering forward on his knees.

"Remember, when you go to your Ka, look for the two black cats. Follow them. They will take you to me. We can resume our game. And then, I may let you win!”

Caron’s eyes opened to see himself, standing not six feet away, on the empty moonlit streets of Oaxaca. They stood in vast courtyard, midst the moonlit shadows of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption, its facade made of green cantara stone, a volcanic rock, its two immense towers with their carvel portals and arches, teetering before Caron’s wearing eyes, forshadowing the earthquake that would bring down both towers in 1931.

“Who are you?”

“Exactly,” said the man, barefooted, dressed only in a hospital gown and mud spattered grey dress pants. “Who are you?” The man reached into the paper bag he was carrying to retrieve a Webley-Fosbery automatic revolver, which muzzle he pointing directly at Caron’s chest, his arm fully extended.

Caron stood motionless, utterly without fear, as eight rounds discharged without effect. Caron’s eyes closed, only to feel his body shudder at the sound of police and ambulance sirens.

The man’s body lay across the filthy walkway, an emaciated stray dog gnawing at his face. Caron chased off the dog, who continued to circle, then bent down to check the contents of the man’s pockets. A blood soaked wallet. A Canadian passport. He opened the latter to read his name, “Gilles Caron.” There was no time. He dropped wallet and passport onto the mutilated body and ran up Manuel Garcia, his quick steps and racing heart reverberating between the thick adobe and stone walls that closed in on him. His last memory was of seeking out the Church of the Santo Domingo de Guzman, being enclosed in the ornate gold leaf of the interior, rattling the iron gates that protected the interior sanctuaries, until the one gate left ajar for him, allowed his last second escape.

Caron gasped in the horrible awareness of suffocation. The engine room had flooded. The hatch was sealed. He no longer recalled how to breathe. He shot up and groaned. The weight on his chest was unbearable, as if a winged one still rested on his ribcage, an impossible weight. He cleared his throat and forced the dream out and the air into his paralyzed lungs. “Of course.” Of course he could breathe. Another dream. He ripped off his grey cap and threw it at the fan. “Black cats be damned.”

All went black again.

Follow them. They will take you to me.

“Perez,” said the voice in the wall. “Listen to me. Do your hear me?” It was Raquel’s voice. Caron grunted, “What is it?”

“You need to run. The police are coming this time. For real. You need to run.” Then sirens. A banging at the door. “Run!”

Caron gasped and threw off the weight on his chest for good this time. He was himself again.

“What this?” said Beatrice. “Another dream? Why won’t you let me tell you a story?”

“Tomorrow!” shot back Caron. “Tomorrow in the day light. It will be sunny tomorrow. Warm. The sunbeams will fall like rain. We can go for a walk in the Parque Lezama or sit here in the light and I will listen to your story.” Caron rolled onto his side.

Beatrice smiled, as she always did, and went back to sleep on the old mattress their host Carlos had dragged next to the much older oaken chest in his impossibly cramped apartment. Caron had apologized profusely for the short notice and thanked Gardel for his kindness. “We’re even now Perez,” Gardel laughed. “Anything for your little angels. I’ll be at the Cafe de Angelo tonight, and I expect a visit from our friends. They won’t be happy you’ve appropriated their precious cargo.”

“The bastards had it coming.”

Gardel smiled. His melifluous humming, first muffled then gently faded as he closed the door, inserted and turned the key, and melted into the hallway. Alba rushed to the door to put on the chain. She covered her mouth with her two hands, looking back at Beatrice, her voice barely audible. “What now?”

The bastards had it coming

Cissinger’s footsteps could still be heard on the steps when Caron turned to Beatrice and smiled. Her bright green eyes stood out on fair skin. Her smile was bewitching. Her hair was golden blond. She wore a simple, golden-yellow dress provided by her captors. Caron retrieved the key from his pocket and unlocked the chain.

“Don’t be running off just yet. We’re being watched.”

“My, you have changed!” said Beatrice, softly, mildly astonished. Caron glanced back twice, in quick succession as he walked away, not really caring to catch the meaning. He entered the tiny kitchen, placing the kettle on the stove. “I’ll make some coffee. A fine mess you’re in.” He laughed.

The knock on the door was Raquel. It was still some days before her warning through the paper thin wall. She had thus far told Montiel very little, but too much by her estimation. She was right and she was afraid. She closed the door behind her.

“Who are they?”

“Miss Liberman, may I introduce you to my guests, Miss Beatrice Portinari, originally from Malta, and Miss Alba, from Poland. I didn’t catch your last name.” Alba remained mute on a ricketty wooden chair in the corner. “Beatrice, Alba …”. Gesturing towards Raquel, “My neighbour and fellow prisoner of the Abasto.”

“Oh shut up and listen.” Turning, to Beatrice, pausing, feigning a smile, “The pleasure is mutual I’m sure.” Raquel shuffled Caron off into the kitchen speaking softly. “I don’t know why but the police know of the murder in Mexico. They know you. Keep a bag packed and ready to go out the fire escape or across into my apartment. My window will be unlocked. I still have my contacts with the police and will help you if I can. I don’t know why.”

“Neither do I.” Raquel was sporting a black eye, a parting gift from Cissinger. “Oh, perhaps I do,” added Caron. “He has bought himself a bullet in the back of the head. It is just a matter of when.”

“Don’t be foolish. You don’t belong here. Take what you can and leave.”

“Where would I go?” Raquel did not respond. She looked into Caron’s blood shot eyes, shook her head, meditatively, then rushed out without another word. There was a commotion downstairs. Caron assumed she was receiving company.

You don’t belong here

“We’ve met before. Did you know that Perez?” Beatrice sat like a mermaid on the cold wooden floor near where Caron was seated, drinking his coffee, the grey cap back on his head.

“What are you talking about?”

“We were neighbours in Montreal. My family had moved there from France in 1907. Do you remember the walk-up brick row houses with all the stairs out front. Your father brought you and your brother Michel to our house for a May Day party. We were both nine years old, and your father suggested we walk to school together, don’t you recall? You said you loved me.”

Caron sat as mute as Alba had been, although she now occupied herself in the kitchen doing the ironing. Caron found himself standing in a school yard, transfixed by the back of a young lady’s knees, not being able to look away. The brownish redish lines were somehow intriguing.

“Nonsense.” There was no question he was taken with his guest, but thought it merely that infectious smile and those golden locks.

“Who am I then, if you know me so well?”

“Gilles Caron of course. Your mother Annie and my mother Marie were very close. My parents moved back to France with my brother Henri and Phillippe before the war. I stayed behind. You remember none of this?”

“You are talking to the wrong man. Your little friend is dead, his faceless body buried in Oaxaca, Mexico.

“I think not. Do you remember the poem you wrote me, I know the last part by heart:

In the darkness of Night, in my soul purged of Light Where the black son of Cronus rules the Regions of Fright, There suddenly came to my ears such a sound, As when the Lyre of Apollo raised stones from the ground. My heart now so heavy was lifted again, by the sweet ring of Laughter and songs by the Glen. "A company of Thespians? Some Ladies of Court?" Who authored such sounds in my lonely resort? From beyond the dense brush and thistle and thorn Came the clear strain of partiers, soft strings and horn. With the silence of Death, I strained to discover, The cause of this tumult whether mortal or other. What I saw was astounding -- but put me at ease. In the forest of shadows were those same Pleiades. The Attendants of Artemis, by a crystalline Fountain Playing and singing with the Nymphs from the Mountain. No mortal had seen them, these sisters divine. I was the first to do so, from my tangle of twine. But my startling had stirred her -- the Goddess herself, Now standing behind me, enraged at my stealth. The Guardian of woodland, and black creek and Earth, Posed at the ready, an Amazon by birth. I tried then to speak, to explain my position, A grunt, I uttered, and felt an odd disposition. My hands now were hooves, my cap crowned with horn. A man I had been, but a buck now was born. My dogs I hear tearing, brought on by my scent. Not a shepherd or hunter, but prey effort spent. A toy tossed by Titans, their mood harsh to see When ...

Caron interjected. “When who did I see, but my fair Bee-a-tree.”

Beatrice laughed. “Beatree… That’s funny. You made me laugh. You do remember?”

They continued in unison, their eyes locked:

Beauty and Boldness, perfected in Air! The youngest Attendant of Artemis stood there. Transformed by her touch to my plain human form, My dogs now contrite for their actions forlorn. Beatrice would guide me, yet divine she remained. Our love all Eternal, true Happiness obtained.

"Funny that,” said Caron. “I’ve definitely heard it before. Something I stole no doubt.

“You were awful in the end. You called me ugly and stupid. I wasn’t good enough for you. You stopped going for walks with me. I couldn’t get you to leave your room. Remember, you would yell, ‘Go Away!’ You were always reading. You never even said goodbye.”

“Now, you are starting to persuade me.”

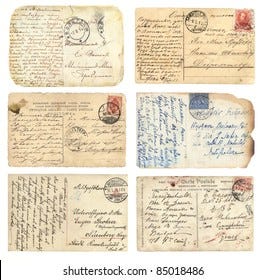

Beatrice put her hands on his knees, looking deeply into his blood shot eyes. The postcards. You must remember the postcards from Lyon?”

“Gilles! Is that you?”

Caron turned to see a familiar face, as he turned down the long, dark lane to Gardel’s appartment.

“It’s Ali, you remember me don’t you? Your guide! The one who wouldn’t stop talking! Your dear friend from Ek Balam? You remember the twins? The jungle? The lovely Ellen James?”

“No actually.” He lied. “What do you want with me Mr. Ali?”

“So formal. No need for that. The Doctor sent me. You remember the Doctor surely? He saved your life.”

“If you call this being saved, you can tell your Doctor to Go to Hell. Goodbye.” Caron knew he could never leave Beatrice and Alba.

“Wait! Wait! Please listen!”

Caron stopped and turned, his right hand index finger touching the handle of the revolver in his coat pocket, where it rested, awkwardly. “Well?”

“The police are coming. Lieutenant Montiel, you know him. He detained me. He asked what I knew. I told him nothing. I didn’t tell him I have been following you and know where you are hiding. But it’s just a matter of time. But don’t worry. I have in my pocket two tickets aboard the SS Asturias from Buenos Aires to New York on its return passage to Southhampton. It leaves at 5 pm tomorrow. Your troubles are over. I also have your new papers. All official, real! No one can stop you. The Doctor has seen to it all. He will meet us at the pier. He will give you back your memory. He has the cure.”

“And whose name is on those papers you have in your pocket.”

“Well, ‘Gilles Caron’, of course. No one is going to stop a dead man.” Ali chuckled like Renfield.

Caron removed his spectacles, revealing those self-same blood shot eyes, his hairline well receded, his brown hair speckled with grey. He placed his latest draft article for the law review to the side, and looked back at the old gothic grandfather clock in his office, as its tubular chimes began to ring 10, the heavy metal dial creaking and hissing. He paused and retrieved from the lower desk drawer to his right a small envelope containing six postcards. The envelope was post marked “Lyon France”, with a return address of a “Beatrice Portinari”.

The note on the cards stated, “Dear Gilles, it has been such a long time. Hope you are well. Miracle of miracles. Found in an open-air antiques sale near the Bastille. You will remember these from the war. Enjoy. We will talk soon.”

The first was sent at Christmastime in 1914, from his mother, Annie, to Louise Portinari. Posted in Montreal with the brief message “Joyeux Noel et Bon Souvenir”.

The second, was posted in Lyon Terreaux (a post office) in July 1915 by someone called Jeannine and addressed to Annie. Beatrice’s mother was Jeannine. She was working in a French hospital in Lyon, perhaps the Desgenettes military establishment. She thanked Annie for her interest in “her soldiers” and for taking care of Beatrice.

The third, also addressed to Annie and Beatrice from Lyon. The author was her brother Henri who indicated he was recovering well from his wounds. “I hope to see both of you soon at the end of this terrible war.”

Caron tossed the fourth and fifth letters asside and read from the last, dated May 2016 and also addressed to Annie from Jeannine, who was now living in a small town of “6,000 souls”. The spring weather was good. Passage had been arrange for Beatrice on the S.S. Melita. She was going home.

Caron crushed his grey cap in his hands. “Let me be the stones,” kicking at the ground.

Beatrice led Caron between the rows of tipa and jacaranda trees first planted by landscape designer Charles Veerecke to beautify the grounds of the Lezama Park in the San Telmo district. Caron’s eyes followed every motion from his peripheral vision, for any hint of Efron or Cissenger’s goons. They would be looking for them.

“Aren’t you ever afraid?”

“Of what? No one can touch us here. It’s like what you said. It’s where the sunbeams fall like rain!”

This is a work of fiction. Although its form, content and narrative may at times suggest real people, real documents and records, autobiography or that the work is historical non-fiction, it is a product of the imagination. Space and time have been rearranged to suit the convenience of the book, and with the exception of public figures, any resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental. The opinions expressed are those of the characters and should not be confused with the author’s.