For more on the Antiquity Dealers, click here

“As-salamu alaikum, my dear Ali.” Degrelle rose from his antique desk, in his antique shop near the Valley of the Kings. Rays of light illuminated the streams of sparkling dust, like daggers, piercing through the opening in his front door, left ajar, joining those stubborn, transient rays dashing through the torn curtains of his shop’s large storefront window.

“Wa alaikum as-salam and Bonjour!” responded Degrelle’s partner, Ali El Arabi, smiling, moving deftly to his right, cane in hand, ducking under the rows of suspended pocket watches that hung from the shop’s low paint-chipped ceiling. Ali’s ample white beard gave him a warm and grandfatherly appearance, although his dusty red fez and black western style suit with vest, made clear he was a man of business and of considerable means. Ali kissed both of Degrelle’s cheeks, lightly, making two kissing sounds.

“Please, please, sit down my friend! Take my chair,” to which El Arabi, obliged with pleasure, and there, deposited his rotundity, removing one shoe so as to massage his right foot. “The desk belonged to Muhammad Ali Pasha, you know.” Degrelle, still wearing the same galabeya robe, in which he had greeted Howard Carter the day before, sat down in the chair in which Carter had so recently been sitting while Degrelle inspected the two inconsequential bronze black cats. Degrelle deposited his two elbows onto his desk, forcefully, then brought his hands together with a slap to both cheeks, his look playful, even childish.

“What have YOU for ME, today dear friend?” He leaned forward.

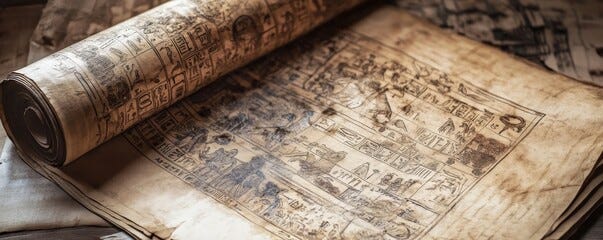

“Papyrus!”

“Papyrus?”

“Yes, Papyrus. Our old thief tells me it is most likely from the scribe of Queen Nefertiti, stepmother to this boy king. Given the Englishman’s grand opening, it might be an opportune time to dispose of it to some of our foreign guests at a premium.”

“What does it say?”

“If I knew that, Eduard, I wouldn’t be here,” he belowed, removing his second shoe. The single sheet of papyrus emerged from between two sheets of cotton, the distinct smell of shellac, applied to prevent deterioration, filing the room.

“No, no, just leave it to me,” shot Degrelle, removing the top layer of cotton so as to fully expose the papyrus sheet, which he took to be about 15 centimetres in width and 20 centimetres in height. He left this little treasure on the bottom sheet of cotton, which he pulled towards him across the table by pinching the nearest corners with both thumb and index fingers.

“Remarkable,” whispered Degrelle. “It’s a hymn!” Degrelle’s eyes moved down the text with escalating rapidity, his mind racing, looking increasingly desperate and uncomfortable, a bead of sweat rolling down his left cheek.” Degrelle’s snake-like scent for opportunity was remarkable and, indeed, unteachable. It was more instinct inherited than anything that could be explained by reason or experience.

Year 12 of the Reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten, Third Month of Peret, Day 5

“What is it?” said El Arabi, releasing his left foot to the wooden floor, which struck with sufficient force to cause pain.

O Miw, blessed guardian of the hearth,

“Yes, yes, yes…”. Degrelle well knew ‘Miw’ was the Egyptian word for cat. A passage further down caught his eye.

I, Imhotep, scribe and servant of the Lady,

Offer this prayer upon the reed and ink,

That the sacred black cats of Bubastis may multiply,

That their spirits shield us from chaos,

That their forms guide us to your Auru.

“The Field of Reeds,” Degrelle thought to himself. “Your paradise. My tomb.”

“Now, that is most unusual,” Degrelle muttered. The cartouche, an elongated oval used to enclose the names of gods, or royalty, contained that name, ‘miw’: the owl, the reed, the quail chick, the seated cat, its tail curled upwards. “Impossible. This must be fake.”

“I assure you, it is not. You know me well enough. I am never fooled. It’s real.”

Degrelle froze. Staring blankly across the table at El Arabi, absorbing the unasailable truth of what had just been stated.

“Still, cats are not royalty,” Degrelle thought to himself. He spoke aloud. “They are revered but not gods. No scribe, let alone a scribe to the Queen, would make such a mistake, would ever place the word ‘cat’ inside a cartouche. And then, to do it twice? Side by side? Two cartouches, two cats. Elevated to gods… or to …”

“…. Royalty…” He paused. “Royalty, to what end?” Degrelle froze again, this time only for a flicker of an instant, an indescribably short moment in time, then shot up and ran to the phone, lifting the receiver. “Operator, get me the airport. Luxor airfield. Yes, it’s urgent.”

“Who is this? That’s fine. You know Ferguson? The pilot. Yes, yes. The Scotsman, yes. I need to speak to him … I see. When? I see… uh huh. Thank you. No, nothing else. Thank you.”

Degrelle replaced the receiver, with incredible delicacy, as if it were made of crystal. In doing so, he used only his index finger and thumb to hold the phone handle, and thus, from that perspective, it appeared as if it were coated with a noxious substance. Forcing a snake-like smile, he looked back at his partner. “His plane, his Sopwith Camel, left 15 minutes ago.”

“What is so important about this Ferguson?” asked El Arabi, rubbing his sore left foot. “Who is on that plane? And what does any of this have to do with my papyrus.”

“Not who,” said Degrelle. “Not … who. What. It’s what he is carrying that concerns me. That concerns us.”

“And what is that, if I may ask.”

“Indeed you may, my dear friend. And this WILL be of interest to you. What this Ferguson carries as cargo on this plane are two black cats retrieved from the tomb of this boy king, only days ago by our Mr. Carter and which have come, quite miraculously, into my possession and care.”

“I see. Yes, I see. As miraculous as my papyrus?”

“A hymn indeed. My friend, I intend to take another look at these cats. A very close one.”

JP’s gaze moved up from the living motion of those brown or red ants, in the sandy earth at his feet, pursuing their inevitable course in the shadows of the living and the dead. Still sitting there on Irene’s favourite bench, now of steel and cedar, his black trench coat draped over his shoulder. He noted to his left, across Peel Street, a prominent Maple tree, at least 40 feet in height, its trunk thick and sturdy, adapted to withstand the abuses of man and winter alike. Its neighbour, planted along the sidewalk in a small green space, an Elm, with its distinct vase-shaped form, a rarity these days due to the ravages of the great plague, the Dutch Elm disease. “You are a survivor my friend, I like that,” JP thought to himself.

“Mr. Caron, is that you?” came a hesitant voice behind him. He turned and was visibly startled by the long, hooked nose, witchlike, and closely set grey eyes, perhaps more corpselike, leaning over the bench into him. JP instinctively recoiled, then assumed his standard lawyerly manner. “That’s my name, Jean-Philippe Caron. What can I do for you?”

“I am sorry to bother you Sir, but do you remember me? We spent a day together. You asked me all those questions, and I gave you all those answers, and they were true, you know.”

JP paused, trying to exhaust his memory. “I’m sorry, you must be mistaken.

“Alison Turnbull. It’s Alison. You do remember me I’m sure. Do YOU know the Doctor?” The effort to produce words caused visible pain in this specter, the voice that she was able to force out seemed to cause her hands to contort and twist, as if operating on some imaginary objects, or trying to strangle some invisible tormentors. “I saw you sitting here by his office. You’re a lawyer. You must know the Doctor.”

“Turnbull, my God,” JP thought to himself. He did remember. He had conducted a day long discovery of this Plaintiff in 2026 before Justice Singh. But, back then, she had been pasty faced, round, albeit overdiagnosed and highly medicated, but still well nourished, at 5’3”, weighing about 160. This skeleton was a mere shadow. JP knew she was in her early 40s, but she looked much older. What hair remained on her pink blistered head was grey and disheveled. “What the hell happened at that pain clinic?” The settlement had provided ample funding for cognitive behavioural therapy, counselling, massage, physiotherapy, injections, pharmaceuticals of all descriptions. “I guess pharmaneuticals weren’t the only drugs she ended up taking,” his experience told him.

She clutched a torn cotton bag tightly to her breast. JP noticed that she wore the remnants of what she had been, frayed, dirty black yoga tights and white tank top, fitting so poorly there was little left to the imagination, except an overwhelming compulsion in the observer to call an ambulance.

“I am sorry, I don’t know your doctor, whoever that may be. Sorry.”

“But he’s over there, in the Hill House, he is always there,” grabbing JP’s arm and pointing to its locked iron gate. “You see I have to get into the Institute, I must. But they won’t let me in. They say I have to wait. They readmitted me into the Program, you remember, for my pain …. but now the Doctor says I have to wait. Perhaps you can help me get an early appointment. And I have been waiting so long.”

JP stood up, faced his ghostly questioner and then, slowly, backed away, his palms open. “Sorry Ms. Turnbull. There is nothing I can do for you. Look, go see your doctors, your therapists, and listen to them. They know what’s best for you. That’s their job. I’m not your lawyer. If you have one, talk to him. Sorry and good luck.” JP turned and walked away, putting on his trench coat as gravity carried him back down Peel. He slowly, almost imperceptively, zigzaged his walk to allow his peripheral vision to do its work. Alison Turnbull was nowhere to be seen. Alison Turnbull was no more.

Irene looked out from the balcony of her new home and took in the panoramic view of her city, Montreal. She was alone, again, in the ‘mansion’ Michel insisted she needed, she deserved, their newborn baby girl required. He had also retained a nanny, cook and maids to attend to their every need, especially when he was away, as he invariably was. “Always some business, somewhere, some new dig, some new acquisition, something urgent with Courville.” She didn’t trust that crook . She told Michel it was too much, too big, too cold. “I want to stay in my old home. I’m not alone there.”

“What are you talking about!” screamed Michel. “You’re always alone. That’s your problem. You’re spending time talking to ghosts. It’s making you sad. The deal is done. You’re moving and that’s that. My boys will come for your things tomorrow. Take the damn clock with you if you want,” he laughed. “We’ll have parties, you’ll make new friends, you’ll be happier than you’ve even been in your life! I promise.”

“Another one of his promises. Always promises.” Irene could hear her mother’s clock chiming, chiming, especially in the darkness of night, a sound only she could hear. And those footsteps. Would they follow her, she wondered.

“You know what,” interjected Michel. “I’ll keep the old place so you can visit, how’s that? For old times sake.”

The price Michel paid made even his old pals Cotroni and Courville blush. Michel had single handedly moved the bar for the most expensive home ever sold in Quebec. The 10-bedroom, 10-bathroom ‘Timmins Estate’ on Sunnyside Avenue sat on 43,000 square feet of prime real estate in the heart of the city. The stone mansion was built in 1910 for Lt.-Col. Charles A. Smart, a politician, military man, mining investor, banker, and entrepreneur, its design, inspired by English architecture of the 18th century. The mansion had been owned by mining and railway titan Jules Timmins, and the name stuck. The architects, Ross and McFarlane, also designed the former Eaton’s building in Montreal. McGill architecture professor Percy Nobbs was retained to design some of the courtyard features. Michel’s favourite Nobbism (as he liked to call it) was Nobbs’ bleak, gothic, wrought iron fence. “Let’s see the Dubois Brothers drive through that.”

It was an exquisite sunny July day, not a cloud in the sky. She could see none of it. Her eyes were open, but those two black dogs were at her feet, making every step laborious, holding out the light and directing every sense inward. She could hear them growling in the attic. She told Michel the mansion he had bought her was full of rats, so they put in traps. But Irene was only deceiving herself. She knew the truth. All she could see was the iron gate of the Hill Clinic, and beyond, the buildings of the Institute, static, colourless, motionless, nameless, a black extended complex of windowless watchtowers, and the black oaks that bekoned. “I must see the doctor.” She handed off her wailing child to her staff, Lise and Pierrette, both dressed in black. “Take care of it. I have a headache.”

She told the doctor she didn’t like the Chlorpromazine, an early neuroleptic. He prescribed it during her pregnancy. It made her nauseous. She would wake to the chiming of the bells and pace the mansion, every room, on every floor till dawn. When she tried to sit down, her feet would tap uncontrolably and then the back spasms, terrible back spasms. “No more! Doctor please.” The Doctor obliged. Years later, JP recalled that his mother suffered from arhythmia, suffered from terrible allergies and caught cold after cold. She drank and became increasingly distant. No one knew why, and no one cared to ask, and all the Doctor’s records were destroyed by then, even if they had.

“Fifteen years, Doctor, and I think I am getting worse,” dropping her face into her hands weeping, utterly despondent.

“Well, I have to say the results are disappointing,” added the Doctor without emotion. “You are suffering from a maladjustment to motherhood, a character neurosis, but that may just be a veneer. We must dig deeper. Perhaps another course of thirteen electro-treatments.”

The Doctor smiled and moved towards his patient. “My Dear,” lifting her head up from her palms, tenderly, with his left hand. “Don’t worry, haven’t I always been here for you?”

“But I have failed, all this time, and I just can’t.”

Pouring two glasses of red wine, then sitting down next to Irene, who was wearing a modest light blue dress. The Doctor wore a black tuxedo. “Here drink, drink,” pouring the red wind into her lovely little mouth, then running his thumb along her lips. “See, isn’t that better?” His hand stroked her back, then stopping at her waist, he pulled her in close. “You have always made me happy, you know that.” Irene turned away and covered her eyes.

“I have a meeting with the Directors tonight. Black tie. Perhaps you’d like to join me?” At 52, the Doctor had retained much of his youthful energy. He boasted a full head of grey hair and a broad white beard. On his rounds, he remained an imposing figure, forceful, good-humoured and fast talking. He’d always been pot-bellied, but carried it well, like he had earned it. When he spoke, his intelligent black eyes were transfixing. It was as it he were reading your soul and the subject became paralized, remaining perfectly still, as if awaiting the final judgment.

“Don’t be silly, I am not dressed for that,” responded Irene. And what would Michel say?”

“Michel? I am not sure you are aware that since you married, I require his signature to treat you. A husband must consent to his wife’s treatment. Michel is a bit old fashioned and is overly cautious. But I would never let minor legalities get between me and my patient. Between you and I. So I have been signing for him. So I guess you could say, I am Michel?”

“I need my sleeping pills.”

“Of course, of course, here,” pulling a packet from his pocket. “The secret of sleep in a capsule.”

“Come tomorrow, early! I have something special for you. Something truly remarkable.”

“Oh, yes, thank you Doctor. You are all things to me.”

The bond between patient and doctor is then unbreakable.

“I don’t want it! Take it away!” Irene threw the painting against the wall shattering the frame.

“Are you insane! That’s a Modigliano! What’s wrong with you?”

“Insane, yes, insane, insane,” throwing herself on the couch in tears.

Michel was appalled. “What is going on? I’ll get a doctor!”

“NO DOCTOR!” Irene shot back, softening, reigning in her fury. “I’m sorry, really I am. I was just thinking of my parents,” she lied. “Oh yes, let’s go for a walk, that’s all I need. I suppose I missed you,” she lied again. “You are always away.”

“I have an idea. Let’s go down to my antiques shop on Rue Notre Dame. I have something to show you that will cheer you up.”

The year before, the Doctor had moved the psychotherapy unit from the Hill Clinic to the new wing of the old Ravenscrag. The T-shaped wing was three stories high, but its true marvels were located in the 9-subterrian levels. The Doctor escorted Irene by the elbow to reception. “This will be your home away from home while Michel is travelling. And when he returns, we will introduce him to the new you. Above the entranceway, was carved the latin word, “Spero” (I hope).

“Let me introduce you to my assistant, Mr. Snead. He will give you a tour of the facilities and show you to your room.” Snead was short, thin and pale. His hair was jet black with long grey sideburns. He rubbed his chapped hands compulsively, without pause. Irene noted that his nails needed trimming and the cuticles had an unpleasant pink hue, as if he enjoyed soaking his hands in bleach. At his touch, Irene felt her body elevated and propelled down the stairs to the first lower level. “The pleasure is all mine I assure you,” said Snead out of turn. Snead took Irene to the lounge, the beauty parlour, the snack bar and the dinning room, all the while explaining in excruciating detail how he had become a vegetarian, how he met the Doctor at his clinic in Mexico and how honoured he was to become his technician. “I prepare the tapes you will see … you will hear.”

On the second lower level, Snead introduced Irene to the art therapist, Mrs. Mercury. “Do you like to paint?” she inquired. The room was covered in childlike art, table and chairs all paint stained, some easels still displayed canvases, in various states of completion. “Where are the patients?” asked Irene. Mercury sat silent, motionless, the paleness of her alabaster skin in stark contrast to her long straight black hair and black dress. “Do you like to paint?” she repeated. Irene noted three cages of song birds. Two contained living birds, source of a modest amount of gentle chirping, pleasant to her ears. The third cage was silent. The two yellow birds lay dead at the bottom. Irene turned abruptly and left, Snead shuffling closely behind. He turned back at Mercury and smiled.

Irene sat on the edge of her bed on the lowest level. She wore a blue hospital gown. The Doctor would be there soon enough. The hall was full of voices and faint mutterings. She slipped from her bed barefooted and moved to the door and pushed it open. Across the hall, a familiar face from the clinic. It was Diane (pronounced Dee-ann). She sat in a wheelchair, motionless, her eyes open, but unaware.

“What happened to her?” asked Irene visibly shocked “The sleep room,” responded the attending nurse. “She is responding wonderfully.” We are discharging her today to the Verdun Protestant Hospital. The nurse walked away, clip board in hand.

“Diane, Diane, can you hear me?” Irene kneeled and shook her shoulders. Diane could neither speak nor control her bladder or bowels, as the smell emanating from her made perfectly clear. She had lost her mind. Irene knew perfectly well that Verdun was for the “hopeless cases.”

“Irene?” came a voice from behind. It was the Doctor.

“Is this your remarkable treatment? Is this what you have planned for me?”

“Don’t be silly. This patient is a schizophrenic and has responded as well as could be expected to a chemical straight jacket. Your case is entirely different. Come now, let’s get started.”

“No, let me out!”

“Grab her!” Snead and two rough looking gentlemen in black seized and carried Irene to the bed, strapping her down, placing a cotton gag across her mouth. The Doctor approached with syringe in hand. “This won’t hurt a bit. Pleasant dreams.”

Haven’t I always been here for you?

Irene was to be discharged. “It was clear,” the Doctor told her, she was “simply unmotivated to get better.” She was “choosing not to get well.” He had “other patients who needed him.” He never wanted to see her again.

Irene stumbled down Peel Street, alone. The two things she needed most in life were gone: her sleeping pills and the Doctor’s presence. She tried several times to see him, but could never get past reception. On this last occasion, Irene had worn the red dress that Michel had given her. It was a tight fit after the pregnancy, but she managed with some effort to slip in, her beauty retained. The lipstick she chose was blood red and richly applied. He would see her this time. She was wrong.

Irene sat at the kitchen table in her mother and father’s old home, still wearing the dress, her lipstick smudged, her hair in disarray. The first flickers of grey. Michel had been true to his word this time, had kept the old house and given her the keys. It remained modestly furnished.

“I had a hunch you’d be here,” grinned Courville, dapper as always, standing in the doorway, next to the tattered curtains and stairway to her father’s room. Over his shoulder, in the driveway, two men in grey trench coats paced along side a black car, its motor left running. “I’m in a hurry. Is Michel here? We have a meeting with the Doctor?”

“The Doctor? …. No, but he’ll be here later. Tell me,” said Irene. “Where is the Doctor?”

“At the Ritz Carleton.”

“What room?” she smiled lightly. “Don’t worry, I won’t tell anyone else?”

“Maybe I should wait?”

“Don’t be silly, the room?”

“237. Tell Michel to hurry. The meeting starts in an hour. The Ministry people will be there. They will all be there.”

The Doctor sat in the adjoining lounge wearing white. The men sitting about him, taking in his every word, wore black. Courville and Cotroni stood behind with some of their men. The Ministry team were making their way into the lounge, as was Messieur G and his wife. The ceilings were high, the sash windows drawn closed. The rich wallpaper featured subtle damask designs, painted in soft muted sage green. The small coffee table where sat the Doctor was of mahogany. The Doctor smiled drinking cognac from a snifter.

“Psychic driving is what I call it. My paper is, ‘Automation of Psychotherapy’. The patients are put to sleep with my injections for days, weeks, years if I have to, until they are ready to listen. They listen to the tapes to implant the message. The bond between patient and doctor is then unbreakable. This I believe is the “unknown force” that turned Cardinal Mindszenty into a mere zombie, an automaton confessing to crimes he had never committed. We can duplicate the results and counter …”

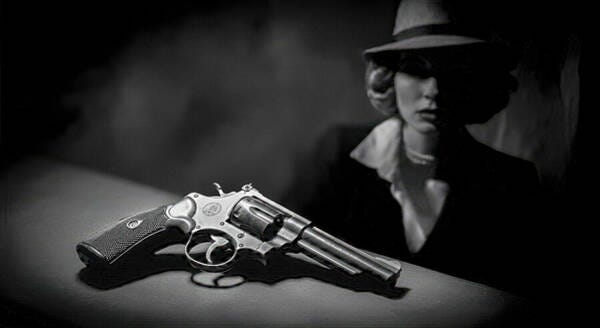

The first blast from the Smith & Wesson .357 Magnum Revolver shattered eardrums, the collective gasp that followed had barely expired when a second round shattered the bulb in the lamp directly behind the Doctor, slicing his right ear lobe.

Michel seized Irene’s wrist with his left hand and directed the muzzle to the floor before removing the gun from her hand with his right, placing it on the table. She did not resist. He had seen her enter the Ritz Carton as he exited his cab, and while he raced after her yelling, she had ignored him. Cotroni and Courville reholstered their pistols, seeing that Michel had matters in hand.

Irene wore Michel’s red dress, her lipstick had smeared across her left cheek. Her eyes were black and fixed on the Doctor, who began to rise from his chair. A distinct stream of red poured from his left wrist pooling on the floor. The left side of his jacket and left sleeve were being transformed by a river of crimson.

“Doctor, my poor Doctor, you are hit!” said Messeur G who knelt down beside him.

“Now, Michel, what are we going to do about this?” said a figure in black from the darkest corner of the room.

“I’m taking her home, you bastards,” was all Michel had to say.

This is a work of fiction. Although its form, content and narrative may at times suggest real people, real documents and records, autobiography or that the work is historical non-fiction, it is a product of the imagination. Space and time have been rearranged to suit the convenience of the book, and with the exception of public figures, any resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental. The opinions expressed are those of the characters and should not be confused with the author’s.